How many years of underperformance must you endure before you’re justified in giving up on international stocks?

Many of you are wondering since, contrary to endless recommendations from retirement financial planners to be internationally diversified, U.S. equities continue to outperform. This year it is not even close: The S&P 500’s

SPX,

-2.27%

year-to-date return is 26.3%, versus just 11.0% for MSCI’s Europe, Australasia and Far East Index (as measured by the iShares MSCI EAFE ETF

EFA,

-2.69%

).

This year is hardly the exception, however. Over the last decade the S&P 500 has doubled the annualized return of the iShares MSCI EAFE ETF, 17.2% to 8.6%. And over the last 15 years, the S&P 500’s annualized return is nearly three times larger, 10.5% to 3.7%.

For this column I am reviewing, once again, the case for international diversification, looking to see if anything has changed that would require altering the traditional financial planning advice.

Diversification

One of the primary reasons why international diversification is recommended is its ability to reduce portfolio volatility. As modern portfolio theory teaches us, to the extent non-U.S. stocks are uncorrelated with U.S. equities, an equity portfolio divided between the two will be less volatile than a portfolio that invests in U.S. stocks alone.

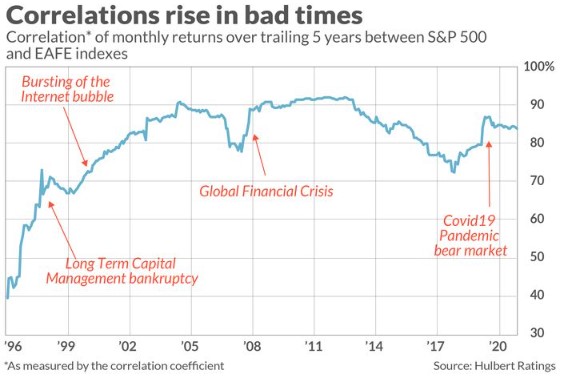

There’s an Achilles’ heel in this argument, however: U.S. and international stocks are least correlated during bull markets, and they become highly correlated during bear markets and crashes. These features greatly reduce the benefits of international diversification, since it would be better if just the opposite were the case.

That’s because we don’t really want diversification when the U.S. market is rising. We instead need it when the U.S. market is declining, and yet that is precisely when the correlation between U.S. and international stocks is highest.

This is illustrated in the accompanying chart, which plots the correlation of monthly returns over the trailing five years of the S&P 500 and the EAFE ETF. Notice that the correlations jump during bear markets.

As an example, consider the stock market’s waterfall decline in February and March of last year, when the COVID-19 pandemic led to a wholesale shutdown of world economies. For the month of February, the S&P 500 lost 8.1% while the EAFE index lost 8.2%. In March, both lost 12.4%. So in those two months international diversification produced no benefits.

Notice also that the correlation between the two markets is much higher today than it was in the 1990s. This is relevant because the traditional case for international diversification is in large part based on historical results from long-ago decades. If correlations are consistently higher today than before, then that’s another reason why the traditional rationale needs to be discounted.

None of this is to say that there aren’t still some volatility-reducing benefits of international diversification. After all, as you can see from the chart, the correlation between domestic and international stocks is not 100%. Nevertheless, it seems likely that these benefits are significantly less than what they were many decades ago.

To the extent your rationale for international diversification was reducing volatility, therefore, you may want to reconsider.

Valuation

The other major argument in favor of international equities is based on relative valuations. Rarely will the U.S. market be the cheapest, so regular rebalancing of one’s equity portfolio across global markets will automatically lead you to periodically sell high and buy low. That’s not a bad idea.

There very much is such an opportunity today. Consider how the U.S. equity market stacks up to those of other countries based on the cyclically-adjusted price/earnings ratio (or CAPE), the valuation ratio made famous by Yale University finance professor Robert Shiller. As of the end of this year’s third quarter, the U.S. CAPE stood at 37.1, higher than all but one other developed country’s market, according to Barclays Indices. Europe’s CAPE is 23.6, the United Kingdom’s is 17.3, Hong Kong’s is 18.0, and Australia’s is 23.4.

Consider what international diversification therefore offers an investor who is worried about valuations. To the extent he focuses only on the U.S. market, this investor has little choice but to build up cash. If he diversifies internationally, however, he can maintain his intended equity exposure while also investing in equities that are more undervalued.

The easiest way for most individual investors to invest in non-U.S. stocks is via an exchange-traded fund benchmarked to a broad index. Besides the iShares EAFE ETF, another often mentioned by the newsletters my firm monitors is the Vanguard Total International Stock ETF

VXUS,

-2.86%.

For a speculative bet on international equities, you might want to consider investing in Turkish stocks. The iShares Turkey ETF

TUR,

-4.27%

is currently recommended by one of the top-performing investment newsletters my firm monitors, even though the country’s equities have had a very bad year. But, in large part because of its poor performance, the country’s equities are hugely undervalued, according to its CAPE ratio. In fact, among the 26 markets for which Barclays Indexes reports a CAPE, Turkey is the cheapest with a CAPE of 7.5—a fifth of what the U.S.’s ratio is.

Don’t allocate more than a small percentage of your equity portfolio to Turkish stocks, however.